rapidly deployed to the Southeast Asia theater of operations where it proved to be even more effective in CSAR.

Still, despite the impressive capabilities that the HH-53B/C brought to bear, it remained deficient in one major area: the ability to effectively perform the mission at night, especially in adverse weather conditions. The Air Force had actually identified the need for an aircraft capable of performing personnel recovery at night and in all kinds of weather as early as 1965, even before the HH-53 had entered service. However, other more pressing needs across the military services took precedence and this requirement went largely unaddressed for two years. | |

The success of the HH-53 in Vietnam made it an ideal platform on which to base the night/adverseweather CSAR capability so urgently needed by the Air Force. |

The inherent risks associated with entering hostile territory by air to recover downed airmen were obvious; attempting to do so at night was borderline suicidal from a flight safety standpoint. Therefore, CSAR operations were typically carried out only in daylight hours. Generally speaking, the only exceptions to this were the precious few occasions when airmen went down in the most benign and relatively risk-free environments in which the chances of enemy contact were slim. Around the clock air operations resulted in a number of downed aircraft during the hours of darkness, the crews of which were usually forced to try and evade capture in enemy held territory until a rescue attempt could be mounted at daybreak. Unfortunately, many of them were unsuccessful and ended up being captured or killed while awaiting sunrise. To further complicate matters, the large array of aircraft needed to successfully carry out and support a rescue mission required extensive planning and coordination among all involved, including the other military services. Careful orchestration by upper command and control elements was | | necessary to de-conflict the sheer volume of aircraft using the same airspace. Furthermore, such missions put an inordinate number of personnel and resources at risk.

All of the aforementioned factors, combined with mounting losses of personnel and aircraft as combat intensified, made the requirement for a more effective CSAR platform more urgent, leading it to be spelled out more emphatically in Southeast Asia Operational Requirement (SEAOR) Number 114 dated April 03, 1967. This requirement called for an aircraft capable of penetrating hostile territory with little or no support, independently locating and retrieving the survivor(s), and affecting a safe and rapid egress back to friendly territory, all under the cover of darkness in all kinds of weather. It became time-critical that such an aircraft be fielded as quickly as possible. The demonstrated capability and performance of the HH-53B/C in the CSAR arena during daytime made it logical to simply modify these aircraft, rather than attempt to develop and produce a whole new aircraft for the mission.

Although the need for an all-aspect air rescue capability had existed for decades, it was only during the years of the Vietnam War that the technology finally came within reach |

The YHH-53H, known as the Black Knight, served as the testbed for both the Pave Low II and III programs. | | to make nighttime adverse weather rescue operations by air a reality. Night vision technology was still in its infancy, but it was maturing at a steady pace and becoming more commonplace on the battlefield as the war progressed. Efforts to exploit night vision capability for CSAR resulted in a number of programs, some of which overlapped and |

An early production HH-53H is seen here during Qualification and Acceptance Testing at Kirtland AFB. | | them into a Night Recovery System (NRS) for the HH-53B/C, hopefully attaining the goals originally set for Pave Star. Tests were conducted in 1971 using a modified HH-53C to verify that performance of the Pave Imp system was at least equal to or better than that of the LNRS. Results were positive, and combat evaluation was subsequently accomplished at Udorn RTAFB during a 90-day period. Although Pave Imp provided a significant increase to existing night recovery capabilities and it was recommended that the system continued to be utilized to the fullest extent possible, the team responsible for evaluating the system made it clear that limitations still existed. They concluded that efforts should continue toward developing an unrestricted all-weather night rescue system.

Barely one month after efforts had begun to establish effective night vision capability through Pave Imp, a Required Operational Capability (ROC) – designated ROC 19-70 Night/Adverse Weather Rescue System – was established on July 23, 1970. As a result of this, direction was given in November of that year to evaluate the use of a Forward |

ran concurrently as research proceeded at a feverish pace. The first effort to introduce a night rescue capability on the HH-53 was initiated on April 25, 1968 and involved a system known as the Limited Night Recovery System (LNRS). This system was comprised of a Low Light Level Television (LLLTV) camera, an infrared (IR) illuminator, a Direct View Device, a Doppler navigation system, a radar altimeter and an Automatic Approach and Hover Coupler System. Operational testing, which was accomplished at Eglin AFB, consisted of 96 simulated rescue sorties. Tests clearly demonstrated that the system did indeed provide a limited capability to accomplish night combat aircrew recoveries over a variety of terrain, and deployment of the system was recommended. Subsequently, incorporation of the LNRS on a number of HH-53s based in Thailand at Udorn Royal Thailand Air Force Base (RTAFB) began in November 1969. Two months later, a total of eight aircraft had received the modification.

Although the LNRS added additional capability to the aircraft, its limitations were recognized early on, and it was acknowledged to be an interim solution. Research continued toward fulfilling the goal of full night/adverse weather CSAR capability, and only six months after LNRS began, an even more ambitious program was born. Running concurrently with LNRS, the Pave Star program had been authorized on October 23, 1968 and initiated on December 16 that year. Its goal was to provide a worldwide, all-weather rescue capability which effectively eliminated the shortcomings associated with LNRS. However, severe cost overruns resulted in the cancellation of Pave Star barely eighteen months after it began. As a result, a reduced program dubbed Pave Imp was initiated on June 22, 1970. It was intended to make use of improvements derived from the short-lived Pave Star program and incorporate | | Looking Radar (FLR) to provide low-level penetration capability for the HH-53. The FLR would work in concert with night vision systems to provide CSAR capability in total darkness under adverse weather conditions in all geographical areas at low level. This program, christened Pave Low, marked the beginning of a revolution in night/adverse weather CSAR capability, ultimately leading to what would become the pinnacle of combat rescue platforms.

The Rise of the Pave Low

The need for low-level penetration while performing the CSAR mission was self-evident. However, it became obvious that sole reliance on night vision to perform the task within acceptable flight safety margins was impractical, particularly given the heavy pilot workload, mental stress and crew fatigue associated with such demanding flying. The Pave Low program aimed to integrate an FLR, more specifically a Terrain- Following/Terrain Avoidance (TF/TA) radar, into the HH-53. This, in concert with night vision systems developed under Pave Imp, would be used to attain the desired capabilities. Practical testing and use of the two systems would prove their codependence upon the other and eventually, the two requirements would be merged, along with other features, into a single package. The initial test concept involved installation of a Norden AN/APQ-141 TF/TA radar system, which was under development for the Army’s ongoing Lockheed AH-56 Cheyenne attack helicopter program. Sikorsky installed the radar, which was modified to provide manual TF/TA steering data to the pilot, in an NRS-equipped HH-53B in June 1972 and valuation was completed six months later. Results were very encouraging, but since the radar was merely a flight test example versus a production ready model, further development costs and program risks to bring this particular system up to production standards |

|

Pave Low III program in May 1975. In order to determine the effectiveness of the systems installed, the YHH-53H was tested extensively under a combined Development Test & Evaluation (DT&E) / Initial Operational Test & Evaluation (IOT&E) program from June 9, 1975 through September 30, 1977. During this time, the test program was interrupted briefly to accommodate a formal roll-out ceremony on September 18, 1975, at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio, home of the Aeronautical Systems Division (ASD) which oversaw the Pave Low program. A crucial aspect of the evaluation involved testing in a number of environments with experienced operational flight crews under realistic mission profiles. One of the locations selected for this was Kirtland AFB, New Mexico. During testing there, one crew was unexpectedly afforded an opportunity for a real-world rescue when | |

The spacious cabin of the Pave Low provided plenty of room for passengers, mission equipment or additional fuel.

|

they heard radio traffic regarding the crash of an HH-3 in a canyon located south of the base. Departing the test range, they used their on-board systems to race to the area and locate the downed helicopter and its crew within ten minutes.

At the conclusion of the evaluation, not only were all major objectives accomplished, but the final results were very impressive. All crewmembers who participated in the evaluation indicated unequivocally that the Pave Low III system provided the first true capability to accomplish the CSAR mission under conditions of total darkness and marginal weather. Recommendations for | | improvement were made, however, regarding the equipment used to pinpoint and positively identify the survivor(s) on the ground. Nevertheless, the system had demonstrated an unprecedented ability to accomplish what had been virtually impossible less than a decade earlier.

As a result of the successful evaluation of the Pave Low III, a revised PMD was issued on April 29, 1977, authorizing procurement and installation of the Pave Low III system in eight HH-53C aircraft. Approval was also given to modify the prototype to production configuration, making a total of nine HH-53H aircraft. |

All structural modifications and installation of subsystems would be carried out at the Naval Air Rework Facility (NARF) at Naval Air Station (NAS) Pensacola, Florida. This was done to reduce costs and risks in regard to technical and logistics support since all major overhauls and depot maintenance on H-53 helicopters throughout the military services were already being performed there. The NARF received its first HH-53C for conversion on August 23, 1977. Nineteen months later, on March 13, 1979, a formal ceremony was held at NAS Pensacola during which the first operational Pave Low III helicopter was rolledout in front of an enthusiastic crowd of distinguished military and civilian personnel. At the time, the aircraft had been given the unofficial moniker “Black Knight,” a name coined by personnel in the Specialized System Program Office at ASD which managed the program. | |

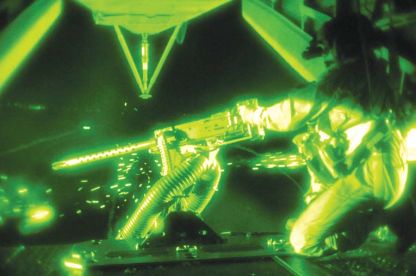

From his position on the open rear ramp, the tailgunner had a very wide field of fire from which to suppress threats.

|

They had picked it as a reference to their legacy of work in years past on other nighttime-oriented military aircraft, such as the Lockheed AC-130 Spectre fixed-wing gunship. Additionally, the original test aircraft for Pave Low II and III, wearing an overall flat black paint scheme, had been adorned with an emblem consisting of a chess knight centered within a white circle. However, the Air Force never adopted the name or the symbol, nor did it ever bestow an official nickname upon the aircraft. Although the Pave Low name technically referred to the specialized systems installed on-board the HH-53, the term soon became synonymous with the aircraft itself.

As modification of each airframe was completed, the helicopters were delivered to Military Airlift Command (MAC) for Qualification and Acceptance Testing, beginning in April 1979. From there, the Pave Low III entered service at Kirtland AFB. The total number of HH-53H Pave Lows to enter service was eleven, nine of which were converted from a mix of HH-53B/Cs, and additional rebuilt CH-53Cs. While at Kirtland, the first realworld rescue mission to be flown by an operational HH-53H took place on January 11, 1980 approximately 15 nm west of Albuquerque. The successful response to a privately-owned light aircraft which crashed in adverse weather at night marked the first use of an operational Pave Low III helicopter. Although this mission took place in peacetime, the potential for a combat mission surfaced only a few months later. World events made the mission assignment to MAC short-lived, as the ongoing Iran hostage crisis prompted the Air Force to transfer all Pave Low III aircraft and resources to Tactical Air Command (TAC) in May 1980. After the failed | | attempt to rescue the hostages only a month earlier under Operation Eagle Claw, leaders had considered use of the Pave Low III in a second rescue attempt. However, a second attempt proved unnecessary, as the hostages were released before a second operation could be implemented. Nevertheless, the functionality of the Pave Low system had been proven, and the Air Force had finally attained a much-needed capability.

Expanding Missions and Capabilities

Consideration of the Pave Low for rescuing the American citizens held captive in Iran highlighted a new role for which the aircraft was ideally suited. The ability of the Pave Low to covertly penetrate hostile territory at high-speed, low-level and long range had natural applications in support of Special Operations Forces. Recognizing this, the decision was made to expand the HH-53 mission to include infiltration/exfiltration and resupply of friendly forces deep within enemy-held territory. The Pave Low offered a degree a flexibility to the Special Operations mission which was unmatched by fixed-wing aircraft. Its ability to take off and land virtually anywhere provided tacticians and planners a number of options which were previously unavailable. In essence, the Pave Low would become a true Special Operations asset, extending well beyond the original CSAR mission requirement developed nearly two decades before. Accordingly, the mission design series designator was changed in 1986 from “HH” to “MH” to reflect the expanded roles and missions inherited by the Pave Low. The increased emphasis on Special Operations justified further upgrades in mission equipment, which were initiated under the Constant Green program that same year. In the meantime, the |

Demonstrating its impressive agility, an MH-53J is seen here skimming

the treetops…a task usually performed in the dead of night!

| | with an additional thirty-one examples being added to the inventory by way of converted HH-53Bs, HH-53Cs and CH-53Cs. That same year, in a move designed to better align the MH-53J with its new multifaceted mission, all Pave Lows were transferred to the newly-formed Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC).

Suited to the Task

The basic design of the H-53 proved more than adequate for adaptation to the CSAR and Special Operations missions. The twin T64-GE-100 engines provided an abundance of power to the 72.25 ft diameter six-bladed main rotor and the 16 ft diameter four-bladed tail rotor. In addition, the dual engine arrangement provided an added margin of safety over single-engine designs. The spacious cabin could accommodate up to 32 personnel or a variety of cargo, depending on the mission, while the hydraulically operated rear ramp made onloading and offloading of cargo, equipment and personnel a quick and easy task. The retractable tricycle landing gear configuration facilitated easy taxiing and ground handling. Large cambered sponsons on either side of the lower fuselage housed additional internal fuel. These sponsons were fitted with cantilever fairings known as “gull wings,” which served as attachment points for externally mounted 650 gal auxiliary fuel tanks, collectively providing an unrefueled range of about 600 nm. If necessary the range and endurance could be extended even further by use of an extendable inflight refueling |

MH-53H became fully immersed in the shadowy world of Special Operations, leading it to become the first Air Force helicopter to be fully cleared for operation with Night Vision Goggles (NVGs).

As each MH-53H underwent modification, it emerged as an MH-53J Pave Low III Enhanced. Externally the MH-53J was almost indistinguishable from the H-model, as most of the changes were internal. Features introduced with the J | | probe fitted on the starboard side of the nose. An automatic hydraulically-actuated blade-folding system for the main rotor and a folding tail pylon, both of which were retrofitted beginning in the early 1990s, facilitated stowage and handling when transporting the Pave Low aboard a Lockheed C-5 Galaxy or Boeing C-17 Globemaster III. |

model included integrated digital avionics, upgraded radar and night vision systems, improved secure communications, additional titanium armor, provisions for an internally-carried 600 gal fuel bladder, and an uprated transmission. In addition, more powerful engines were introduced in the form of 4,330 shp General Electric T64-GE-100 turboshaft engines (replacing the 3,936 shp T64-GE-7A previously used). The first MH-53J was rolledout on July 17, 1987 at the Naval Aviation Depot (formerly NARF) at NAS Pensacola, achieving Full Operational Capability (FOC) at Hurlburt Field, Florida in 1988. Training for Pave Low pilots and aircrew members was accomplished using a fleet of five TH-53As, all of which were converted Sea Stallions acquired from the Marine Corps in 1989. By 1990, all remaining MH-53Hs had been upgraded to MH-53J standard, | |

Inflight refueling was a key factor in the Pave Low's ability to penetrate deep into hostile territory. |

Despite its large size, the Pave Low was incredibly fast and maneuverable, with a top speed of 170 kt. Its ability to perform nap of the earth (NOE) flight in rolling and mountainous terrain, day or night, in any weather, was made possible not only by its advanced sensor suite, but also by its inherent agility. Pilots would typically fly as low as 50 ft over the highest obstacle in order to avoid detection on radar and to minimize exposure of the aircraft to enemy air | |

Insertion of Special Operations Forces took many forms, one of which was helocasting as seen here. | | helicopter was defended by a dedicated aerial gunner through a cabin window behind the cockpit. The tail gunner provided suppressive fire for the rear sector of the helicopter, along with a significant portion on either side, from the open rear ramp. The establishment of integrated crews, a battle-proven concept since the days of World War II, was practiced among the Pave Low community and was |

defenses, a technique known as terrain masking. Despite a gross weight of up to 50,000 lb, the Pave Low’s robust construction and more-than-adequate power margins allowed pilots to enjoy a virtually unrestricted flight profile.

In addition to aggressive low-level flying tactics, a variety of on-board equipment and systems served to protect the Pave Low from the inevitable dangers lurking in hostile territory. To defend against threats at the objective, any combination of three GAU-2B/A 7.62 mm miniguns or GAU-18/A .50 cal machine guns were mounted one each in the port window, starboard crew door and rear ramp. Chaff and flare dispensers were mounted at various points on the airframe and AN/ALQ-157 IR jammers were placed strategically on top of each gull wing to defeat incoming heat-seeking missiles. In addition, a comprehensive Electronic Warfare (EW) suite was fitted to counter other threats.

Even with the vast array of sophisticated on-board systems and sensors, close and continuous crew coordination was absolutely essential in Pave Low operations. In the early days of the Pave Low I test program, twenty-five experienced HH-53 pilots were interviewed as part of a 10-month study to identify operational CSAR problems relating to cockpit controls, displays and crew station areas. Results of this study were assessed to determine their impact on operational mission effectiveness. Since that time, crew coordination and training was perfected to a synergistic level in which crews placed total trust in one another in order to survive and accomplish the mission. While pilots concentrated on flying and navigating to and from the objective, they relied heavily on the lead flight engineer – seated between and slightly behind them – to monitor aircraft and system performance throughout the mission. When approaching the objective and once on-scene, a second flight engineer would swap between operating the 600 lb capacity rescue hoist and providing defensive fire suppression from his position in the starboard crew door as needed. The port side of the | | proven to significantly enhance their combat effectiveness and survivability. The extremely low altitudes which comprised the Pave Low’s primary operating environment made situational awareness by all crewmembers a critical element in mission accomplishment, particularly since approximately 95% of all Pave Low missions were flown at night. A true team effort became paramount when arriving at the rescue site and entering into a hover or landing to retrieve personnel in total black-out conditions. While on-scene, the use of NVGs by the crew was an absolute necessity to ensure visual awareness of ground obstacles such as trees, rocks, electrical power lines or other hazards.

“Pave Low Leads”

While supporting various operations around the world throughout the 1980s, such as Operation Just Cause in Panama in 1989, Pave Low crews became very adept at their job and were soon recognized throughout the military as some of the best in the business. Their reputation as such made them and their aircraft some of the most sought-after assets in the U.S. military inventory. This accolade came to the fore in 1991 when the Pave Low was selected to lead the initial strike package into Iraq to initiate Operation Desert Storm. In order for coalition air forces to successfully penetrate Iraqi air defenses and destroy key targets with the best chances of success, it was necessary to open a sizeable gap in the Iraqi air defense radar network on the Iraqi/Saudi Arabian border. Although the McDonnell Douglas (now Boeing) AH-64A Apache attack helicopter could bring plenty of firepower to bear on the targets, it was not adequately equipped (at the time) to accurately navigate the vast, featureless desert terrain of Southwest Asia for long distances. Therefore, it was decided that a task force of Apaches would be led in tight formation by a pair of MH-53Js using their highly-accurate Global Positioning System (GPS) and INS equipment. The unparalleled accuracy of the on-board |

The Pave Low, seen here performing a fast rope insertion, wore a three-tone European Igreen/gray paint scheme throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. | | execution of this critical mission played a pivotal role in the success of the war, inspiring Pave Low crews to adopt the self-assured motto, “Pave Low Leads.”

After leading the very first mission of the 1991 Gulf War, the Pave Low performed countless other missions, many of which remain shrouded in secrecy even today. Along with the clandestine insertion and extraction of Special Operations Forces throughout the theater of operations, the Pave Low also took part in some highly publicized operations, one of which was the rescue of a downed U.S. Navy fighter pilot: the recovery of Lieutenant Devon Jones was noteworthy not only for having been performed under enemy fire in broad daylight, but also for being the first successful Air Force CSAR mission since the Vietnam War.

Soon after the Gulf War of 1991, Pave Low crews again found themselves in the forefront of regional conflict in places such as Liberia, Haiti and various other locations. When |

A select few MH-53Js wore a two-tone desert camouflage scheme known as Asia Minor during Operation Desert Storm. | | war erupted in the Balkans in 1995, Pave Lows were some of the first Air Force assets placed on alert as Operation Deliberate Force commenced. A few years later, during Operation Allied Force, they were involved in the high-profile rescue on March 28, 1999 of the pilot of a downed Lockheed F-117A Nighthawk who evaded capture in Serbian-held territory for more than six tense hours. Two months later, a Pave Low rescued the pilot of a downed Lockheed Martin F-16C Fighting Falcon, evading heavy enemy fire for two hours in the process. Aside from performing the traditional CSAR mission, Pave Lows carried out numerous Special Opeoperating deep behind enemy lines duringrations missions in support of troops |

systems allowed crews to arrive on-scene within plus or minus 30 seconds of the scheduled time. Acting as | | operations in the Balkans. |

pathfinders, the Pave Low crews would drop chemical lightsticks at pre-determined waypoints along the route to the target, allowing the Apache crews to update their on-board Doppler navigation systems accordingly. In the early morning hours of January 17, the mission took place exactly as planned with the Apaches reaching their objective and scoring direct hits on the radar and communications sites, opening a 20-mile corridor for coalition strike aircraft. The flawless | |

From the mid-1990s through the end of its career, the Pave Low adopted a single overall color known as Gunship Gray. |

Pave Low IV: The Last

Generation

After a number of upgrades and improvements over the years, the Pave Low appeared in its final variant as the MH-53M Pave Low IV. Initiated in 1997, the Pave Low IV program aimed to provide the aircraft with enhanced threat detection and defensive capabilities while providing crews with improved situational awareness of the battlefield. Modification of the aircraft, twenty-five in total, took place between 1999 and 2001. The primary internal difference in the M model was the addition of the Interactive Defensive Avionics System / Multi-mission Advanced Tactical Terminal (IDAS/MATT). This advanced system provided crews with near

| |

The ability to compress the Pave Low for carriage aboard large cargo aircraft allowed rapid deployment to any continent on the globe. |

| | highly-tasked platforms in the Air Force. In total, only 41 airframes received the Pave Low modification. Its heavy use in all theaters of operation around the globe was taxing on the airframe. To maximize its usefulness and longevity, the entire Pave Low inventory underwent a Service Life Extension Program (SLEP) beginning in the mid- 1990s, receiving numerous upgrades and new components. The SLEP not only allowed the Pave Low to continue flying despite its considerable age, but it also provided enhanced mission capabilities.

Having seen its first major conflict during Operation Allied Force in 1999, the Pave Low IV |

Shipboard operations provided an added

measure of flexibility to the Pave Low mission.

real-time intelligence and threat information from various off-board sensors, allowing them to update their flight profile en route and more effectively avoid known air defenses. Aside from internal changes, another feature of the Pave Low IV was the AN/AAQ- 24(V) Directed Infrared Countermeasures (DIRCM) system which could better protect against IR-guided weapons. Additionally, a fully automatic mode was added to the chaff and flare dispenser system to more effectively counter radar-directed and IR-based threats. As a low-density/high-demand asset, the Pave Low was one of the most | |

About 95% of all Pave Low missions took place at night, a feat at which the aircraft and her crews excelled. A Stokes litter is being winched into position during this night time exercise. |

10 | | VERTIFLITE Winter 2008 |

again entered large-scale combat when the Global War on Terror (GWOT) began at the start of Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan in September 2001. Eighteen months later, when the invasion of Iraq occurred in March 2003, the Pave Low was again at the forefront of combat during Operation Iraqi Freedom. Both of these conflicts were significant for their heavy emphasis on Special Operations, a task for which the Pave Low and its crews proved immensely effective. As in previous conflicts, the Pave Low was often – not surprisingly – one of the first assets present within a given theater of operations.

From the Battlefield to the Boneyard | | airframe had no structural fatigue problems. Even as late as June 2008, Pave Low crews were engaged in low-level flight training in the mountains and valleys surrounding Roanoke, Virginia.

The final operational combat mission for the Pave Low took place on September 26, 2008 during a logistical resupply and passenger movement mission supporting Special Operations Forces in central and southern Iraq as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom, bringing an end to a distinguished career of nearly 30 years. Fittingly, the mission took place under the cover of total darkness. Like many before them, most of the last Pave Lows to see action were transported directly from the theater of operations to the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group (309 AMARG), affectionately known |

Ever-rising maintenance costs and man-hours were key factors in the decision to retire this impressive but aging machine. | |

| as the “Boneyard, adjacent Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona. Those that were not taken to the Boneyard found their way to museums around the country, ensuring their place in history as a symbol of freedom and the heroes they supported. As the drawdown of the Pave Low occurred, some units chose to commemorate the service of of this remarkable aircraft with formal ceremonies honoring the type. One of those, the 20th Special Operations Squadron (20th SOS), held the distinctive honor of being the last unit to operate the Pave Low. |

The Pave Low was the final and most versatile variant of the Air Force H-53. |

Given adequate funding and no end in sight for the Pave Low mission, the Air Force had originally planned to retain the aircraft in service possibly as late as 2014. However, the inevitable rise in maintenance costs and the increasing number of maintenance man-hours required per flight hour to keep the Pave Low flying took its toll. This, combined with ever increasing reductions in funding, meant that the Pave Low IV program turned out to be the last major upgrade for the type. Even as the first MH-53J was retired on January 4, 2007, the Pave Low remained a highly effective, fully mission-capable platform with no operational flight restrictions, and the | |

A formal retirement ceremony, attended by scores of military and civilian guests, was held on October 17, 2008 at Hurlburt Field, Florida. Pilots, aircrew members, maintainers and various others who were involved with the Pave Low at one time or another all gathered to bid a fond farewell to the machine they knew and admired. In the Hurlburt Field Air Park, an MH-53M now sits immortalized on permanent display.

As the decision was made to retire the Pave Low and the type was gradually withdrawn from service, the Air Force endeavored to introduce the Bell Boeing CV-22 |

Osprey tiltrotor into full operational service as a partial replacement for the Pave Low. While the Osprey’s superior speed and range will allow it to perform long-range infiltration/exfiltration and resupply, differences in flight profile, performance and capability as compared to the Pave Low will not allow it to fill completely the void left behind by the MH-53J/M. Instead, the remainder of the Pave Low mission will be carried out by Army Special Operations helicopters such as the Boeing MH-47E/G Chinook.

Conclusion

Indisputably, the Pave Low established a solid and well-deserved reputation for performance and reliability among its crews and maintainers. Its high mission-ready rate was a testament not only to the hardworking maintenance crews, but also to the sheer ruggedness of the H-53 airframe. Having performed countless clandestine military operations across the globe, ranging from the small-scale conflicts of the 1980s to the present-day liberation of Iraq and the ongoing campaign in Afghanistan, the Pave Low will be remembered as a true warrior. The “cloak-and-dagger” nature of Special Operations dictates that many of the missions undertaken by the Pave Low and her valiant crews will remain shrouded in secrecy for years to come. Eventually, when these missions are one day made public, the true valor and bravery inherent in the Pave Low community will be revealed. In addition to its secretive wartime role, the Pave Low provided valuable assistance in peacetime disaster relief and humanitarian support missions in numerous places around the world. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Pave Lows provided airlift for equipment, supplies and personnel in the massive relief effort. Even as recently as mid-September 2008, less than one month prior to retirement, a Pave Low was placed on standby to assist the U.S. Coast Guard on a mission to rescue the crew of a Cyprusflagged freighter adrift in the Gulf of Mexico in the midst of Hurricane Ike.

Despite being a conversion of an existing platform rather than one built for the mission from the ground up, the Pave Low had no peer in nighttime low-level penetration capability. The Pave Low was viewed by many as the premier CSAR and Special Operations helicopter, a sentiment enthusiastically shared by virtually all who flew it. Indeed, many crewmembers, both newcomers and seasoned veterans, have proclaimed that the Pave Low was – and will remain – the absolute peak of their career. Even in retirement, the Pave Low leaves behind a legacy as the largest, most powerful and most technologically advanced helicopter ever to fly in the Air Force inventory. In the words of Lieutenant Colonel Gene Becker, Commander of the 20th Expeditionary Special Operations Squadron (20 ESOS) in Iraq which flew the final Pave Low combat mission, “She goes out, as she came in – the very best.” | |

The Pave Low served admirably in the deserts of Southwest Asia, flying its final combat mission in Fall 2008.

Further Reading

• Donald, David (Managing Editor), Sikorsky H-53,

World Aircraft Information Files, Bright Star Publishing

plc, London, England, 1997.

• Donald, David (Editor), U.S. Air Force Air Power Directory,

Aerospace Publishing Ltd., London, England,

1992.

• Gambone, Leo Anthony, Pave Low III: That Others

May Live, Aeronautical Systems Division History

Office, Wright-Patterson AFB, OH, 1988.

• Gunston, Bill (Consultant Editor), The Encyclopedia of

World Air Power, Crescent Books, New York, NY, 1980.

• Hunter, Jamie (Editor), Jane’s Aircraft Upgrades 2007 –

2008, 15th Edition, Jane’s Information Group Ltd.,

Coulsdon, Surrey, United Kingdom, 2007.

• Reed, C.M., H-53 Sea Stallion in Action, Squadron/Signal

Publications, Inc., Carrollton, TX, 2000.

• Taylor, John W.R. (Editor), Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft,

Jane’s Publishing Co. Ltd., London, England,

1970 - 1992.

• National Museum of the United States Air Force:

www.nationalmuseum.af.mil.

• Air Force Link: www.af.mil.

• The Pave Cave: www.thepavecave.com.

• DefenseImagery.mil:

www.defenseimagery.mil/index.htm. |

12 | | VERTIFLITE Winter 2008 |

As the sun sets on the Pave Low, the legacy left behind will remain one of the great success stories of Air Force Special Operations.

|

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to personally acknowledge and thank the following individuals for their valuable assistance and generous contributions in preparation of this article: 1Lt Lauren Johnson and TSgt Kelly Ogden, 1st SOW Public Affairs Office; Capt Brian Daniels, TSgt James Rhodes, SSgt Matt Garcia and SrA Jack Price, 20th SOS; SSgt Jamieson Ross, 1 SOHMXS; Capt Sean Borland, 71st SOS; and Tom Lawrence, Sikorsky Aircraft. | | About the Author

Ray Robb served in the United States Air Force for

ten years. He currently works as an Air Force civilian

at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio, and is an avid aviation enthusiast, photographer, and historian. He is a frequent contributor to Vertiflite. |

|